Southern Nevada and the world watched as Las Vegas hospitals and doctors operated and cared for the wounded on Oct. 1 and subsequent days, and they’re getting high marks for their performance for handling the worst mass shooting in modern U.S. history.

While 58 were killed — nearly all succumbed to their wounds at the scene of a country music concert on the Strip — more than 500 people were injured, and most passed through nine of Las Vegas’ 14 hospitals. More than 200 went to Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center, and more than 100 went to University Medical Center — the city’s two main trauma centers for handling emergency cases.

The hospitals and the medical community are evaluating their performance for a wider report about lessons learned. That information will be disseminated across the country as doctors, nurses and administrators appear at panels in the coming months to share with professionals in their fields.

“From each mass casualty event in the country from Virginia Tech to the movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, Boston, Newtown (Connecticut) to San Bernardino, each of those, as a hospital and trauma system, we have learned how to better prepare ourselves,” said Todd Sklamberg, CEO of Sunrise Hospital. “We have a responsibility to do the same, and we will be digging deep and strong into our program and response to determine what could have been done better and understand best practices and share those transparently across the country. No one else has seen what we saw.”

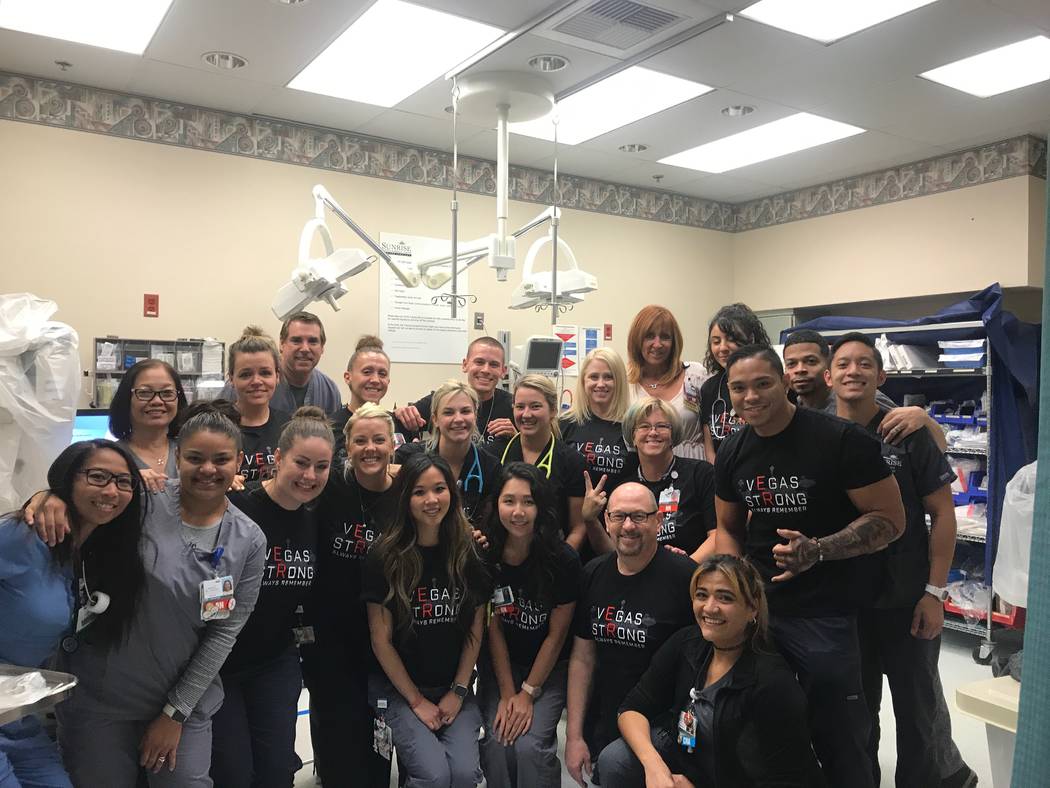

The Southern Nevada medical community has appreciated the recognition it’s gained this month.

UMC and Sunrise have received posters from school children, thank-you cards, calls, gifts of flowers and food from celebrities, hospitals and medical professionals from across the country.

Trauma surgeons and other medical professionals have been honored at physician award dinners and at sporting and other public events. The recognition of how they made Las Vegas proud means a lot to doctors and has helped change the perception of medical care here, said Dr. Joseph Adashek, president of the Clark County Medical Society. He cited how doctors rushed to hospitals from all over the valley to take care of people.

“You know the old joke about how to get the best care in Vegas is to go to the airport? I don’t think there’s any of that anymore, especially after Oct. 1, knowing more than 500 people were injured and 99 percent of patients who came in injured ended up surviving to whatever hospital they were brought to,” Adashek said. “That’s amazing, since there were so many critically injured patients. It’s a proud moment for doctors here.”

Bill Welch, president and CEO of the Nevada Hospital Association, said the health care professionals responded “extraordinarily” based on the volume of casualties brought to hospitals that would “overwhelm most communities” and how they met their immediate needs in 12 hours. He gives the medical community’s response an A grade.

“We were able to respond and pull in the resources to address all of their needs in a very short time,” Welch said. “I know every hospital went on full capacity, and hospitals were taking patients that they normally wouldn’t because the trauma centers were full. I can’t say enough how the medical community responded, and we’re getting national recognition for our ability to respond.”

Once hospitals complete their internal review, they will be shared with one another how they responded and what the challenges were, Welch said. They will look at what they did well and how they would do something differently in the future, he said.

“I would say I’m encouraged to see all of the training and drilling that we do worked, and this is a perfect example of it,” Welch said. “We in Nevada should feel fortunate to have dedicated health care professionals. All the hospitals have activation protocol where we start calling their staff and nurses and doctors and allied health professionals, and most of the staff responded without being called at 100 percent capacity across the whole valley. That speaks volumes of their commitment to meet the needs of this community.”

Doctors credited the triage system employed by Sunrise and UMC — where patients were separated into categories of head, chest, abdomen and extremity wounds and went through a second process of evaluation by neurosurgeons and other surgeons — with playing a role in the successful response.

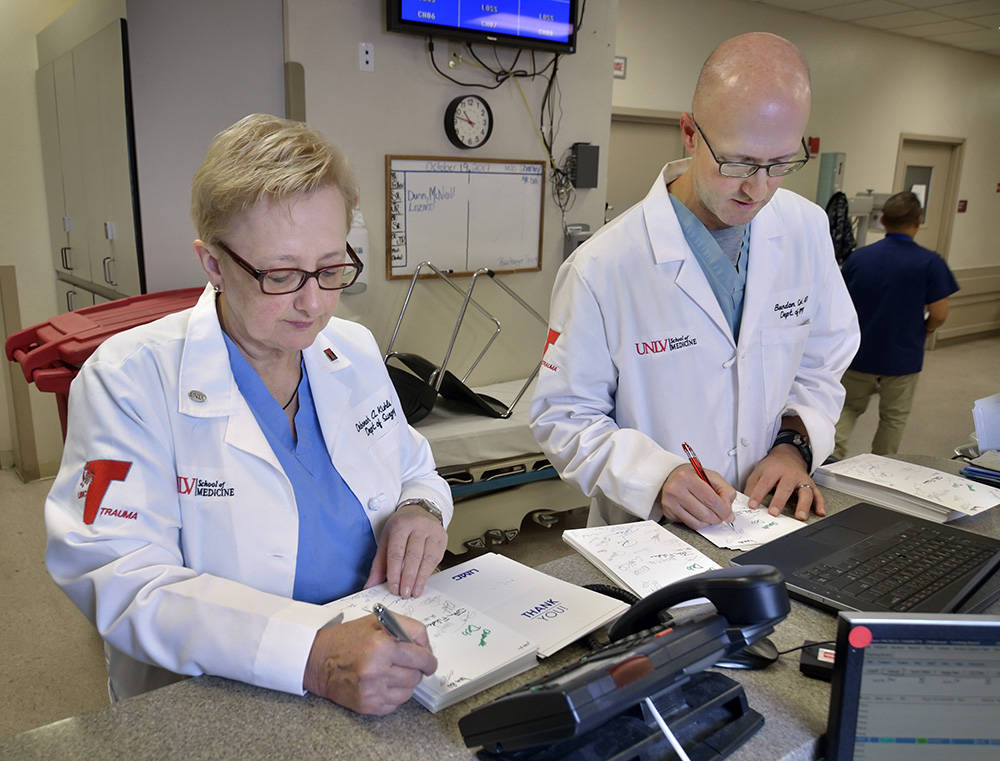

“I would say that it speaks well to a trauma center that we didn’t have anybody die that had a potentially survivable injury,” said Dr. Deborah Kuhls, chief of critical care in the surgery department at UMC and professor of surgery at the UNLV School of Medicine.

Jerry Reeves, corporate vice president of medical affairs for HealthInsight, a community organization dedicated to improving health care, said how Las Vegas medical community handled the mass shooting is impressive, since it’s not a city with five medical schools and multiple medical centers that people fly to from all over the world.

“I think this clearly clarifies that Las Vegas is a place to receive excellent care,” Reeves said. “If you can have that kind of massive terror and everyone who arrived at the hospital that was alive and is still alive, man, I’m telling you that’s a lot. This is clearly clarifying how really impressive medicine is delivered in this place when the going gets tough.”

The biggest lesson learned is that “practice makes perfect” with the training for mass casualty responses that has been coordinated for years, Reeves said. There are two countywide drills a year, and most hospitals conduct at least two drills a year on their own.

“We think about the Boston Marathon bombing and how impressive Harvard and Mass General Hospital were in that setting,” Reeves said. “That was minor compared to what happened here. It puts things in perspective from the language that has been used when talking about health care in Nevada for too long. It’s time to move history forward to what is present than what’s past.”

Mason VanHouweling, CEO of University Medical Center, called it the “darkest day in health care for every hospital in the state.” He also said mass casualty drills to test the system at all hours of the day made a difference. He cited what was learned from the 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting for adjusting plans, communications and supplies.

“I’m proud of the performance,” VanHouweling said. “Many lives were saved because of the way we have drilled. I think we in the health care community have known how good our health care system is, and I think, unfortunately, through this event, the nation has seen how good we are. We are a model in many ways on dealing with a major event and surge of patients. I think it said a lot about our community. It’s tightknit, and one bullet isn’t going to break the spirit of our community.”

Sklamberg said 120 of the 211 patients treated at Sunrise Hospital had gunshot wounds. Thirteen people came in as fatalities, and two had injuries that weren’t survivable. Another one had extensive injuries and died in the operating room, he said.

“Our drills never centered on 200 patients arriving in an hour,” Sklamberg said. “But we got more than 100 providers in within 45 minutes and 30 surgeons within an hour to accommodate the volume that came in. I’ve never been so proud of how an organization responded as Sunrise did.”

Sunrise Hospital had many as 10 operating rooms going at once. UMC, which had fewer patients, had six going at once.

Hospitals didn’t have the luxury of deciding how patients were dispersed, since 75 percent of them went to hospitals in private vehicles, rather than ambulances, Welch said. Many simply went to the closest hospital.

Dr. Douglas Fraser, vice chief of trauma at UMC and section chief of trauma at the UNLV School of Medicine, said that while many concertgoers directed themselves to the nearest hospital based on traffic patterns, there were communications over emergency scanners that UMC was closed and no longer accepting patients. That could have led to more patients getting directed by ambulance to Sunrise Hospital, and he expects the issue to be addressed when the Clark County Fire Department issues a report.

“The pandemonium that ensues in a mass casualty means very often there is misinformation,” Fraser said. “The one take-home that we should have from this is UMC is open all the time for every injury. We never close for trauma. We had teams of surgeons waiting for people, and they were not coming because they had heard we were closed. Sunrise did a phenomenal job. I just feel we were sitting there waiting to help more and had the ability to do more. I think it would have helped the overall system” if patients were distributed more.

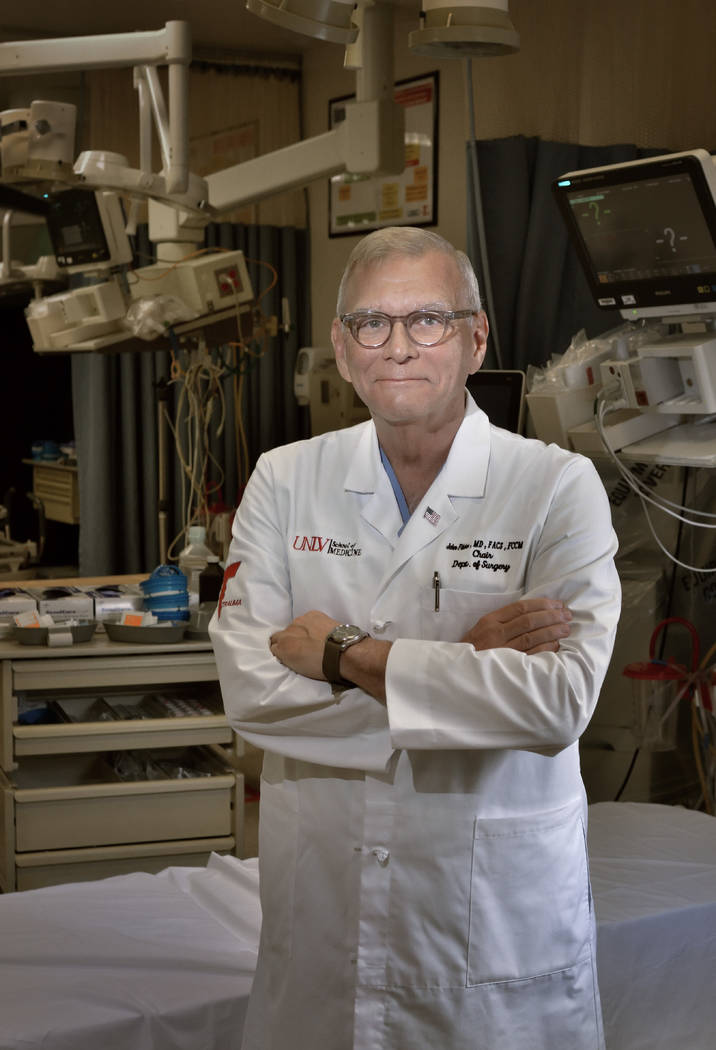

Dr. John Fildes, medical director of UMC’s trauma center, said there will always be a maldistribution of patients in mass casualty incidents.

“I talked to friends in San Francisco where they prepare for earthquakes, and they have a plan to level-load their system so if one hospital gets too many patients, there are actually ambulances or buses that go around and pick up patients at one hospital and move them to another. We should probably have a discussion about level-loading hospitals during a disaster.”

Fildes said he has seen plenty of mass casualties in his 21 years at UMC, including a tourist bus accident and a woman driving her car on a sidewalk along the Strip. The best comparison to the mass shooting would be the MGM Grand fire in 1980 that killed 85 people and injured more than 500. People fled the scene and directed themselves to the hospital for treatment like they did in the mass shooting, he said.

“They went to hospitals based on proximity, open roadways and available transportation,” Fildes said. “The science of disaster tells us that those who die usually die on the scene, and anyone who is able to leave the scene will do so under their own power. That happened as 22,000 people dispersed and many of the more than 500 injured got themselves off the scene and directed themselves to care. EMS (Emergency Medical Service) did a great job with assets to bring the most critical patients to the trauma centers. But we had surgeons standing by in operation rooms for patients that didn’t come.”

Fildes said there’s “always room for improvement,” but the system didn’t fail that night. He said he couldn’t be more proud of every hospital and trauma center in the valley. Everybody delivered and “did the right thing,” he said.

“Las Vegas needs to understand that there’s no other city on this planet that reacted as quickly or as well to an incident of this magnitude,” Fildes said. “It tells us Las Vegas is one of the best kept secrets in health care, particular in the trauma system, in that every hospital showed its capacity to rise up to take care of patients in an emergency. This is an unprecedented success. To have more than 500 injured and have everybody in bed with a blanket over them by sunup is an absolutely amazing feat.”

Doug Geinzer, CEO of Las Vegas HEALS, a group of more than 600 health care professionals whose mission is to improve the quality of care, said the way hospitals, doctors and emergency medical technicians responded to the mass shooting should show the public not only in Las Vegas but across the country how good the health care system is in Southern Nevada.

“We have some of the best physicians in the entire country,” Geinzer said. “I think our response to the Oct. 1 shootings demonstrated that to the rest of the world. Had that horrific event occurred anywhere else but Las Vegas, the casualty count would have been much, much worse.”

Geinzer said that other cities would have seen more casualties because they don’t have a coordinated trauma-delivery system like the one in Southern Nevada.

“Las Vegas, hands down, has the finest trauma system in the entire country,” Geinzer said. “The reason is simple. We not only treat the 2.2 million population but the virtual population that visits the Strip and has zero inhibitions and does crazy stuff. We see cases no other cities do.”

Geinzer said Las Vegas will share with the rest of the world the “best practices” it learned from the mass shooting, just like it did after the MGM Grand fire.

“Every hotel has fire-retardant systems because of that fire,” Geinzer said. “It was a horrific event, but Las Vegas provided leadership to change the world. I think we will do the same with this.”

Trauma doctors from UMC and Sunrise will be among those lending their support to hospitals and physicians across the country, just like an Orlando trauma surgeon who came to Las Vegas a few months ago, Fraser said. He knows what he will say to them.

“The main message is to be prepared and practice and have a plan,” Fraser said. “If you don’t think it’s going to happen in your city, that would be a big mistake. The other message is that it’s a team effort. Every single person is involved with this. It’s not just trauma surgeons. It’s everybody from the nurses to housekeeping and engineering and biotech supply people and anesthesiologists, respiratory therapists, physician assistants and nurse practitioners. You need to include all of those people in your preparatory plans. All those people have a role, even an operator. You might have to call in extra operators to deal with the call volume.”

The lessons are even being incorporated by the residents, the doctors in training at UMC who participated in the treatment of patients. They will be impacted for the rest of their careers, Fraser said.

“This will permanently put a mark in their training,” Fraser said. “It’s something they will reflect on both good and bad. It let them know they rose to the challenge and could handle that all at once.”