revolution is taking place in medication and the Nevada Institute of Personalized Medicine at UNLV is at the forefront.

The institute, approved in March 2015 by the Board of Regents, focuses on research to discover methods and mutations of genes that are causing human disease. It’s also partnering with the UNLV School of Medicine and Grant a Gift Autism Foundation to open its first medical genetics clinic this summer in Las Vegas.

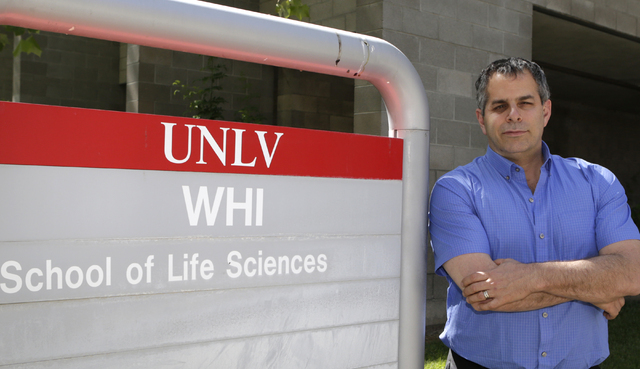

Modern health care relies largely on an expensive “one-size-fits-most” model for diagnosis and treatment that often fails to account for biological differences between people, said Martin Schiller, executive director of the NIPM and a professor at the School of Life Sciences at UNLV.

Personalized medicine is different because your unique genetic makeup – your DNA – already encodes the blueprint for effective treatment and disease prevention, he said.

“NIPM will help move Nevada from the trial-and-error medicine of today to the data-driven decision-making of tomorrow by decoding genomes to predict disease susceptibility, sift through treatment options, and fine-tune drug dosages to minimize adverse effects and help Nevadans lead longer and healthier lives,” Schiller said.

Research in the industry has ramped up and there’s a newer approach to sequencing what’s called the exome of people, Schiller said.

“We have a lot of DNA to sequence,” Schiller said. “During the past four to five years, there’s been between one and two million exomes of people sequenced, and it’s used mostly for discovery but it can also speak to what your health issues are. It can also be used in some cases to diagnosis people.”

Exomes contain all of the regions of the genome that are important in the function of cells and physiology of most diseases, Schiller explained. Once variations are identified, a single change in genetics can be screened and used clinically, he said.

“It has already become the standard of care in a number of areas of medicine and if you’re receiving cancer therapy and if you hadn’t had this done, that’s not modern medicine anymore,” Schiller said.

Medication is another area where genomes can help, Schiller said. About one-tenth of medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration have a genome on the label, he said.

“That means you’re supposed to look at someone’s genetic makeup before you treat them with that drug to decide whether they can tolerate the drug or what dose they should be given of the drug,” Schiller said.

Genetics is important in neo-natal use as well, Schiller said. Many developmental disorders in newborns can be diagnosed using genetics. Doctors can look at a baby’s genes in the mom’s blood, and a general screen for diseases is becoming a routine part of that, he said.

What happens to people as they age is due to two factors – your genetics, what you inherited from your parents, and your environment, essentially what you’ve exposed yourself to, including food, Schiller said.

“Some things you might get are due 100 percent to your parents and genes and some are 100 percent due to environment,” Schiller said. “A car accident is environment, but breast cancer is mutation in genes and severe mutations. There’s nothing you could do. You were always going to get that. Most things, however, fall in a happy medium. Half are due to genes and half to do with environment.”

Some people are genetically prone to constipation, and it could be so severe that it’s deadly, Schiller said. There are ways to know long before something happens to you by starting early and getting more screening, he said.

“Let’s say a mutation says you have a huge increased risk of getting colon cancer,” Schiller said. “Nobody should get colon cancer because we know there’s a screening procedure that if done often enough, means you won’t get it.”

The current recommendation is that the average person gets screened for colon cancer with a colonoscopy at age 40, 50, 60 and 70, Schiller said. But it turns out a lot of people don’t have a high risk, and it’s not necessary to screen them as often, he said. A small set of the population, meanwhile, is at high risk and should be screened as often as once a year, he said.

“It’s a paradigm shift in how we’re doing diagnostic prevention and medicine,” Schiller said.

It’s even been vital for people who are ill and go to the doctor who can’t figure out what they have. Other specialists are consulted and don’t have an answer either, Schiller said. By that time, the condition gets worse, he said.

“There’s a percentage of people who have this and wander through the health care system, and it impacts their lives in very big ways,” Schiller said. “A five-year-old starts getting sick and dizzy and gets to the point where they can’t get out of bed to eat. It won’t go away and primary care, neurology and even the Mayo Clinic doesn’t know what it is,” Schiller said. “This is more common than you think it is. Doing undiagnosed gene genetics, about half of those people you can figure out what they have.”

Getting an exome test by drawing blood and comparing the patient to their parents and possibly siblings and what’s inherited can help determine what’s going on, Schiller said. That helps narrow what doctors need to look at, he said.

This testing will eventually be the future of medicine for everyone, Schiller said.

“We’re getting to the point where we’re starting to get there, but we’re not quite there yet,” Schiller said. “If they have a problem, they should get it but because it’s so new, only a percentage of doctors are recommending this approach that everyone get tested.”

It’s happening at some medical practices, Schiller said. If you have a family history, it’s recommended you get a panel of tests. Instead of getting a whole exome, it may be suggested you do five or six genes involved in colon cancer, for example, Schiller said.

“There’s already a 1,000 panels out there that are clinically validated, and these are used in routine practice already,” Schiller said. “What the exome gives you is the ability to do it all at once. It’s for particular mutations that are already well known, and we know what they do when you get one.”

The American College of Medical Genetics decides which genes should be added to the list. These are genes that if it’s shown you have a mutation in them, you’re going to get a deadly disease, he said.

“There were 56 genes in the list originally, and there’s a second list out which has 110,” Schiller said. “It’s fairly new, but it’s growing quickly. If you analyze someone’s exome and find this gene that says that they will get this severe disease, you have to tell them and recommend they see a specialist right away.”

The list includes genetic cancers and cardiology disorders. Every organ system has a set of genes where there are some disorders, Schiller said.

“One of 10 people will have a genetic disease in their life, and that’s underestimated,” Schiller said. “There’s already 5,000 diseases where we know the genetics, which can be tested for in a single exome test.”

Why not a genome test?

Genome sequencing does all of the DNA of a person. Exome is one percent of that DNA, but it’s the most important part because it’s involved in your health, Schiller said.

“The reason we do exome instead of genome is because if we find a mutation in the genome, we have no context to interpret it. We don’t know what to do,” Schiller said. “If we find it in the exome, we know a lot about that, and we can help connect it with what to do.”

The genome sequencing cost is getting low enough to do the test, but it has been mostly exome testing so far, he said. In research settings, exome testing costs about $700 and genome testing costs about $1,500 to $2,000, Schiller said.

In a clinical setting, it could cost $3,000 to $5,000 for exome testing and an extra $1,000 to $2,000 for genome testing, Schiller said.

“What test you get depends on who the experts are,” Schiller said. “Some of the experts are saying we should only be doing genomes and some are saying we should only be doing exomes. I think as the cost drops, we will be doing genomes in five years. I think either way, it will serve the same purpose. Genomes won’t be overkill in the future, but now it is. It’s not very common you’re going to find something in the genome that’s you won’t find in the exome. You will, but you won’t know how to interpret it.”

Schiller said he believes that everyone should be genetically sequenced at birth because that will help you throughout your life. Parents getting sequenced is “a gift to your children that’s irreplaceable,” he added.

“There is a whole bunch of stuff you can’t figure out unless you compare it to your parents,” Schiller said. “Unless you have your parents DNA, that’s what needed to rule out all of the noise so you can focus in on what’s relevant.”

For those under the care of a primary care physician and meet the criteria, insurance will pay for an exome test. If two relatives died of colon cancer, for example, that would meet the criteria, he said. The patient can take that information and their risk for getting colon cancer and decide the level of screenings they need if it’s beyond what’s recommended for patients on a regular basis.

“That’s why it’s called personalized medicine,” Schiller said. “It’s a blend of your genetics and what risk you’re willing to tolerate, just like you’re evaluating risk for other things you do.”